Frequently Asked Questions

Software & Data Processing

The SeaSave data visualization and processing software relies on a few factors in order to establish communications with your CTD and to process your data correctly. Some issues prevent good data from being displayed, while others will prevent communication entirely. Here are a few of the most commonly encountered issues we’ve seen.

First, since SeaSave uses serial connections, establishing the correct COM port and Baud Rate for your instrument is crucial. Choosing the wrong COM port will give you no communication at all, whereas choosing the wrong baud rate can give you either no response or a set of ‘garbage’ characters as the software attempts to interpret the data. One can think of this as speaking different languages- the baud rate establishes that both your CTD system and your computer are talking in the same language, so matching them is essential. There are defaults listed for most systems, but you can also check your User Manual for options. To identify your correct COM port, use Window’s Device Manager app, which is built in to all Windows computers, to identify the COM port that is added to the list of available Ports when you plug it in to the computer.

Another common real time issue is the Scan Length Error. Our software uses a file that contains your instrument’s calibration and hardware setup information called the .XMLCON. This file is used by the software to determine how many hexadecimal bits per line it should expect to convert. For more information refer to the FAQ “What is a configuration (.con or .xmlcon) file and how is it used?”. However, the CTD is not using the xmlcon to determine what voltage channels or serial data is enabled, those are all controlled via settings in the firmware that you can control. If the number of enabled channels on your CTD doesn’t match the xmlcon, the ‘scan length’, that is the number of bits per line, won’t match either. This causes the error, and prevents any data from being converted. To fix it, compare your xmlcon file to your CTD setup with diagnostic commands like DS or GETHD (refer to your user manual) and ensure that everything on your CTD that is active is represented in the xmlcon.

Another common source of confusion can be how the software maintains the ranges and outputs of displays and plots. You may need to double check if the ranges and variables you’ve chosen match those of your data. One simple way to do so is to look at the converted CNV data’s header, where it lists the range for each column of data under the lines marked with “#span”. If your CTD is connected but your plot doesn’t seem to be updating, this is a great place to start.

Yes, like the HydroCAT EP’s glass bulb pH sensor, the SBE 18 pH probe is capable of running in both fresh and salt water.

If you have questions about your sensors accuracy or storage recommendations or suspect your sensor has lost accuracy, please contact Sea-Bird Technical Support.

The deep SBE41 and SBE61 use the same pressure sensor – a 7000dbar Kistler. And, they are calibrated with the same Paroscientific Digiquartz reference. However, the calibration process is different. A deep SBE41 receives a 2-point sensor only temperature compensation for pressure. The initial accuracy for a deep 41 is +/- 7dbar, typical stability is 2dbar/year. A 61 receives a 4-point temperature compensation for pressure after the instrument is completely assembled, such that the correction includes both the sensor and the electronic boards. The initial accuracy for a 61 is +/-4.5dbar, typical stability is 0.8dbar/year.

The menu to configure the factory parameters you are asking about is accessible through the i*? command. The ? argument for this command will give you a list of all of the arguments to change each individual menu. Let me know if you have any questions about the list of commands in the help menu, and I can try to clarify.

Some cautionary suggestions about changing these parameters:

(1) These parameters should only be changed prior to deployment. Changing them post-deployment could cause you to permanently lose your ability to communicate with the float remotely.

(2) In order to retain Sea-bird Navis warranty coverage, you must provide a log of pre-deployment testing that includes telemetry to your server system after all parameter updates have been performed.

Unfortunately, users cannot currently program their SUNA to start at a preferred time. As soon as the SUNA is powered, the instrument will begin it’s programmed sampling mode on the hour. Users can use the offset feature to change the start time. For example, an offset value of 300 (5 min) changes the start time by five minutes, for example, from 06:00 to 06:05.

The continuous mode setting allows the user to program their SUNA to run continuously for an indefinite amount of time. When power is supplied to the SUNA, it will start data acquisition without an end time or maximum number of frames to measure. In general, we do not recommend this mode for long periods of time because the lamp of the SUNA can burn out. As a general rule of thumb, the SUNA lamp should be replaced when it reaches 750 hours.

The fixed time mode setting allows the user to program their SUNA to run continuously for a period of time or specified number of frames. When data acquisition has completed, the sensor will enter a low-power standby mode.

The periodic mode setting allows the user to select how often, and how long sample intervals are based on frame-based or time-based operation.

For example, if a user would like to program their SUNA to sample every two hours, they would use a sample interval of two hours.

The user would then select either frame-based or time-based operation

For frame-based operation, the user selects the number of light frames the SUNA will sample for.

For time-based operation the user selects how many seconds of light frames the SUNA will sample for.

When the SUNA is powered, the instrument will begin it’s programmed sampling mode on the hour. Users can use the offset feature to change the start time. For example, an offset value of 300 (5 min) changes the start time by five minutes, for example, from 06:00 p.m. to 06:05 p.m.

Temperature and Conductivity are two of the most important values taken into consideration when our instrument calculates the practical salinity of seawater. When one sees a change in a measured value, such as temperature, that change will affect your salinity reading in a predictable way, assuming all else is equal. For instance, in an environment where temperature has begun to drift downward you will see a resulting drift of salinity towards being saltier.

Proper cleaning procedures, allowing your CTD to equilibrate at the surface before a profile, updating your calibrations yearly, and bio-fouling prevention are some ways that you can ensure that your instrument will provide accurate salinity data.

For a more comprehensive look at our salinity calculations please refer to App Note 14, which is hosted on our website.

The back-scattering measurements are a portion of the total beam attenuation coefficient of the water being sampled. The beam attenuation is measured during the back-scattering calibration. Therefore, the range specification on the data sheet for the BB sensor (0 – 3 or 0 – 5 m^-1) refers to the beam attenuation coefficient range of the calibration.

There is a note on the data sheet that further explains the backscattering specification:

*Backscattering specifications are given in beam cp (m^-1) based on the regression of the response of the instrument relative to the beam cp measured at the coincident wavelength using an ac-s spectrophotometer. Scale factors for backscattering incorporate the target weighting function and the solid angle subtended.

How can I use Bottle Summary to output the bottle number as well as the trip order to a .btl file?

Yes, it is possible to include bottle ‘serial numbers’ through the use of a .sn file, which is a user-created file containing information about the bottles you have fired. Creating the file before processing your data in Seabird Data Processing’s Bottle Summary module is necessary for the process to work. If a .sn file (same name as input data file, with .sn extension) is found in the input file directory, bottle serial numbers are inserted between the bottle position and date/time columns in the .btl file output.

The format for the .sn file is:

Bottle position, serial number (with a comma separating the two fields)

Cells that have been contaminated with foreign material generally read low of the actual conductivity. Your zero (in air) conductivity reading is generally unaffected.

The conductivity error due to fouling will generally be proportional to the conductivity value. Conductivity is corrected not as an offset but as a ratio (multiplicative) error compared to a reference.

Salinity is a derivative measurement of temperature, conductivity, and pressure, and should be corrected by adjusting the component measurements. Generally speaking, an error in the conductivity measurement will correlate to a directly proportional error in the salinity measurement.

The temperature and salinity correction for the SUNA can be traced to the experiment outlined in Sakamoto et al. 2009, which is the T/S correction our UCI-based SUNA software uses in post-processing only.

Absorption of UV light in seawater is dominated by dissolved nitrate and bromide ions at wavelengths less than 240 nm. To estimate nitrate, it is necessary to remove the absorption due to bromide. The salinity correction addresses the sea salt extinction coefficients due to bromide. In the real ocean, bromide covaries with NaCl. So, during calibration, we can measure the the bromide absorption due to seawater at one salinity and later predict the absorption due to seawater at any salinity.

Artifical seawater surrogates do not necessarily have the correct bromide absorption to be able to validate the the Sakamoto et al. 2009 salinity correction, so the salinity correction may not product accurate results if your data was not collected in natural seawater.

This modification allows the SBE9plus CTD to accept an RS-232C serial instrument data stream and transmit to the surface.

The acceptable baud rate at the SBE9plus CTD is determined by the EPROM version installed in the modem board. These modem board options include, 9600 or 19200 baud, 8 bit data, and “none” parity. At the surface the SBE11 deck unit will extract the serial data from the standard telemetry and transmit data to a remote host PC/computer via a DB-9 connector on the back panel of the deck unit. This data is transmitted to the host computer at 19200 baud regardless of the serial instrument baud rate at the underwater unit.

The SBE 911plus system was designed with idea that all 9plus would operate with all 11plus deck units. With the modification for serial uplink, however, only a modified 9plus will work with a modified 11plus.

The detector wiring is damaged, especially if the LED’s are still flashing. NOTE: CDOM channels do not have visible LED’s, so, do NOT look into the CDOM LED port to confirm its operation (!!).

The ECO firmware is programmed to output an unchanging “floor” value of output counts, if there is no signal from the detector.

Conversely, if the LED is burned out, one would see a changing serial output count, dithering around the ECO dark count value or showing another ambient light condition/change (i.e. values would be changing 48, 51, 47, 52, etc…).

Whether the tau correction is applied depends on where the system is being deployed.

If the system is to be used in shallow, coastal waters where large vertical gradients that change quickly are expected, the tau correction should be applied, as it accounts for the response time and puts the interface between two different water masses in the right place.

If the system is to be used in deep water (>200 m) where the vertical gradients are small, the tau correction should be turned off – in areas where the gradients are small, the calculation adds more noise.

The measurement range and accuracy of the SBE43 are not definite in discrete units (mL/L, mg/L, µMol/L, etc.) Rather, the range and accuracy specification are expressed as a ratio of the calculated oxygen saturation point. This saturation value depends on the temperature and salinity of the water, decreasing in higher temperatures and higher salinities.

The lower limit of detection of dissolved oxygen concentration is going to be constrained by the accuracy specification, which is a ratio of the calculated oxygen saturation (initial accuracy: +/- 2% of saturation). This saturation value varies depending on the temperature and salinity of the water. Common oxygen saturation values in seawater are in the range of 4-7 mL/L. Using this value as an estimate, you can extrapolate that the accuracy of the sensor in many conditions can be as low as +/- 0.1 mL/L. Therefore, the close you get to zero oxygen concentration, the closer the resolution of your measurement will be to the accuracy spec, until you get below 0.1 – 0.2 mL/L and your measured value is smaller than the nominal error margin.

While the theoretical lower limit of the instrument’s measurement range is zero, the measurement becomes less meaningful the closer your dissolved oxygen measurement gets to 2% of the calculated saturation. For example, if you were in an environment where the oxygen saturation was 7 mL/L but the oxygen concentration measured by the SBE43 was 0.28 mL/L, then your accuracy would effectively be +/- 50% of the measurement.

The command interface is different and not inter-compatible for both devices. The sampling and configuration commands are also not inter-compatible. Because of this, they require different software (i.e. SeaFETCom for V1, UCI for V2).

The SeaFET/SeapHOx V1 has native USB compatibility, while the V2 is an RS-232 only device. The V2 requires a USB-to-RS-232 adaptor to connect to a USB port.

The magnetic switch serves different functions on a V1 versus a V2. The V1 uses it to activate & deactivate the internal batteries, but the V2 uses it to provide sample status.

Oftentimes one will see data in their cast that looks erroneous or out of spec, but reviewing the timeline of each cast and the events which transpired can explain these jumps. If you are starting your cast while your CTD is on deck then the time during which the unit is running in air can be spikey or erratic, but this should be solved after the unit has been fully submerged and the pump has activated. The pump on time setting controls how fast the system will turn on the pump after deployment, so filtering out your deckside data can be done by calculating the number of scans to exclude using your pump on time setting, samples to average setting, and native sampling rate of your CTD.

Bubbles in the flow line can also cause spikes in your data towards the start of your deployment if the system isn’t able to normalize at the surface. We typically recommend units stay near the surface for 2-5 minutes in order to allow air bubbles to escape.

Finally, for additional resources in troubleshooting and smoothing data outliers for your CTD data, refer to our documentation on Seabird University.

Data is stored in a RAM page buffer, which is only written to FLASH when it is full. If the instrument is powered off, samples stored in the partially filled page buffer will be lost BUT the recorded sample number will still be the same. This means that when all samples are uploaded, the last few will be unreliable. The page buffer is 256 bytes. If a sample is 17 bytes then up to 15 samples at the end could be lost.

Our suggestion for how to avoid this problem is that if you want every sample, upload data without power cycling the instrument. Otherwise, plan to log samples for N more than you want to acquire, where N is based on the number of samples required to fill the page buffer.

There are other potential causes, but this is more probable. If this method does not resolve your issue, please contact Technical Support.

When the SeapHOx system loses connection with its 37 SMP-ODO CTD component, the system will report back the measured AND derived values related to that instrument as NAN. As part of this, it will also report its External pH as NaN as the salinity correction is missing the CTD’s input. The external pH requires the CTD’s temperature and salinity input in order to make a valid measurement.

The CTD data- the temperature, pressure, oxygen, and salinity come through this Y cable connection. Check to see if your CTD has lost power (either external SeaFET power or internal lithium AA cells) and stopped transmitting data to the SeaFET. If both the CTD and SeaFET are working the next most likely point of failure is the connection between the two units, primarily due to either an incorrect setup of the communication settings or due to a physical loss of connection.

Inspect your connection for signs of a bad cable, bent or loose pins on your bulkhead connector, or water ingress. For the settings side, refer to the manual and integration guide for the correct settings.

Sea-Bird hosts an FTP (file transfer protocol) site for larger data transfers than are available by standard email. The instructions for gaining access to this FTP site can be provided by Sea-Bird Technical Support upon request. Software that is either no longer provided with new instruments (SunaCOM, for instance) or older versions of software can be found in the associated software folder, though we recommend you try the latest version of any software available on our website.

The spike seen in the pump out phase is due to the commencement of flow and reagents/material that is outside the optical path initially but is swept through the optical path during flush out. The spike is accepted as normal behavior of the system and does not affect data quality.

Whether the tau correction is applied depends on where the system is being deployed.nnIf the system is to be used in shallow, coastal waters where large vertical gradients that change quickly are expected, the tau correction should be applied, as it accounts for the response time and puts the interface between two different water masses in the right place.nnIf the system is to be used in deep water (>200 m) where the vertical gradients are small, the tau correction should be turned off – in areas where the gradients are small, the calculation adds more noise.

CAPO4 is the phosphate concentration that the instrument reports as its measurement. CAPO4 is the calculated concentration of an ambient sample using the CAS slope, where CAS is the manufacturer’s scale factor, which is provided by Sea-Bird. nnVAPO4 is used in a QC process to monitor potential drift or spot pump failures or other mechanical problems. VAPO4 is the calculated concentration of an ambient sample using the VAS slope, where VAS is a variable slope calculated in-situ using the on board standard. VAS is only calculated during the Cal Spike frequency runs, used on subsequent samples between the Cal Spike. So, VAS and VAPO4 are not always good values and can affect whole groups of samples between the Cal Spike runs.nnThe calibration for CAPO4 does not include a variable ambient sample of unknown quantity as VAPO4 does.

A setup file is used by Seasave V7, and by each module in SBE Data Processing, to remember the way you had the program set up. You can save the file to a desired filename and location, and then use it when you run the software the next time, to ensure that the software will be set up the same way:

- A .psa file is created by Seasave V7 to store program settings, such as the instrument configuration (.con or .xmlcon) file name and path, serial ports, water sampler, TCP/IP ports, serial data output, etc. as well as size, placement, and setup for each display window.

- A .psa file is created by each module in SBE Data Processing to store program settings, such as the input filename and path, output filename, and module-specific parameters (for example, for Data Conversion: variables to convert, ascii or binary output, etc.).

If you want to set up real-time acquisition or data processing on more than one computer in the same way, simply copy the file for the desired setup, and transfer it to the other computer via your network, email, a thumb drive, or some other media. Then, after you open the software on the second computer, select the setup file you want to use.

- Seasave V7: Select File / Open Setup File.

- SBE Data Processing: In the module dialog box, on the File Setup tab, click the Open button under Program setup file.

Sea-Bird’s main software package is called Seasoft©.

- Seasoft V2 — Seasoft V2 is actually a suite of stand-alone programs. You can install the entire suite or just the desired program(s).

- Deployment Endurance Calculator — calculates deployment length for moored instruments, based on user-input deployment scheme, instrument power requirements, and battery capacity.

- SeatermV2 — terminal program launcher that interfaces with Sea-Bird instruments developed or redesigned in 2006 and later, which can output data in XML. Can be used with SBE 16plus V2, 16plus-IM V2, 19plus V2, 25plus, 37 (SI, SIP, SM, SMP, IM, IMP, all with firmware 3.0 and later), 37 with oxygen (SIP-IDO, SIP-ODO, SMP-IDO, SMP-ODO, IMP-IDO, IMP-ODO), 39plus, 54 and PN 90588, 56, 63, and Glider Payload CTD. SeatermV2 provides setup, data retrieval, and diagnostic tests.

- Seaterm — terminal program that interfaces with most older Sea-Bird instruments, providing setup, data retrieval, and diagnostic tests.

- SeatermAF — terminal program that interfaces with instruments that provides auto-fire capability for autonomous operation of an SBE 32 Carousel Water Sampler (with an SBE 17plus V2 or AFM) or SBE 55 ECO Water Sampler, providing setup, data retrieval, and diagnostic tests.

- Seasave V7 — acquires, converts, and displays real-time or archived data. Seasave V7 is an entirely new version of Seasave, officially released March 2007.

- SBE Data Processing — converts, edits, processes, and plots data; some of SBE Data Processing’s most commonly used modules include Data Conversion, Bottle Summary, Align CTD, Bin Average, Derive, Cell Thermal Mass, Filter, and Sea Plot.

- Plot39 — plots ASCII data that has been uploaded from SBE 39plus, 39, or 39-IM Temperature Recorder or SBE 48 Hull Temperature Sensor.

- Seasoft for Waves —

Provides setup, data retrieval, data processing, auto-spectrum and time series analysis, statistics reporting, and plotting for the SBE 26 and SBE 26plus Seagauge Wave & Tide Recorder. Also provides setup, data retrieval, data processing, and plotting for the SBE 53 BPR Bottom Pressure Recorder.

Additional software is available to simplify use of coastal instruments:

- Universal Coastal Interface (UCI) —

Provides setup, operation, in-field reference checks, data upload, and plotting for the HydroCAT, HydroCAT-EP, and SUNA.

The configuration file defines the instrument — auxiliary sensors integrated with the instrument, and channels, serial numbers, and calibration dates and coefficients for all the integrated sensors (conductivity, temperature, and pressure as well as auxiliary sensors). Sea-Bird’s real-time acquisition and data processing software uses the information in the configuration file to interpret and process the raw data (sensor frequencies and voltages). If the configuration file does not match the actual instrument configuration, the software will not be able to interpret and process the data correctly.

When Sea-Bird ships a new instrument, we include a .con or .xmlcon file that reflects the current instrument configuration. The file is named with the instrument serial number, followed with the .con or .xmlcon extension. For example, for an instrument with serial number 2375, Sea-Bird names the .xmlcon file 2375.xmlcon. You may rename the configuration file if desired; this will not affect the results.

(Click here to see an example of where to find the serial number on your instrument)

Seasave V7 and SBE Data Processing version 7.20 (2009) introduced .xmlcon files (in XML format). Versions 7.20 and later allow you to open a .con or .xmlcon file, and to save it to a .con or .xmlcon file.

To view or modify the configuration file, use the Configure Inputs menu in Seasave V7, or the Configure menu in SBE Data Processing.

Notes:

- Seasave V7 and SBE Data Processing check that the serial number in the configuration file matches the instrument serial number in the .dat or .hex data file. If they are not the same, you will get an error message. The instrument serial number can be verified by sending the Status command (DS or #iiDS, as applicable) in the appropriate terminal program.

- SBE 16, 16plus, 16plus-IM, 16plus V2, 16plus-IM V2, 19, 19plus, 19plus V2, 21, and 49 — The instrument serial number is the same as the serial number of both the conductivity and temperature sensors.

- SBE 37 (older), 39, 39plus, and 48 — These instruments store calibration coefficients internally and do not accept auxiliary sensors, so they do not have configuration files.

- SBE 37 (newer) that is compatible with SeatermV2 terminal program — SeatermV2 creates a configuration file for these instruments when it uploads data. The configuration file can then be used for processing the data in SBE Data Processing.

- The calibration date in the configuration file is for information only. It does not affect the data processing.

- When Sea-Bird recalibrates an instrument, we ship the instrument with a Calibration Sheet showing the new calibration coefficients (1 calibration sheet per sensor on the instrument that was calibrated). Sea-Bird also supplies a .xml file with the calibration coefficients for each calibrated sensor. The .xml files can be imported into Seasave or SBE Data Processing, to update the calibration coefficients in the configuration file.

— For CTDs: Sea-Bird also creates a new configuration file, which includes calibration coefficients for the CTD as well as any auxiliary sensors that were returned to Sea-Bird with the CTD. If you did not return the auxiliary sensors with the CTD, you need to update the configuration file to include information on the auxiliary sensors that you plan to deploy with your CTD.

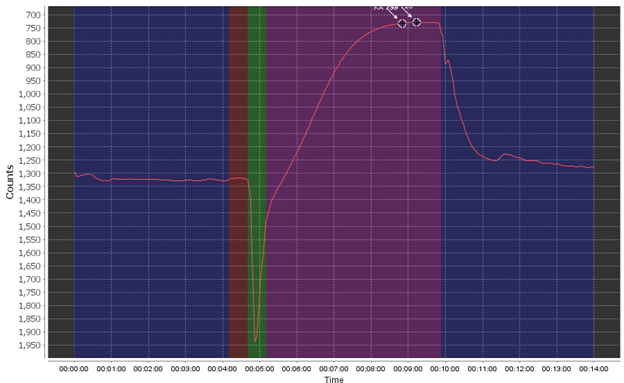

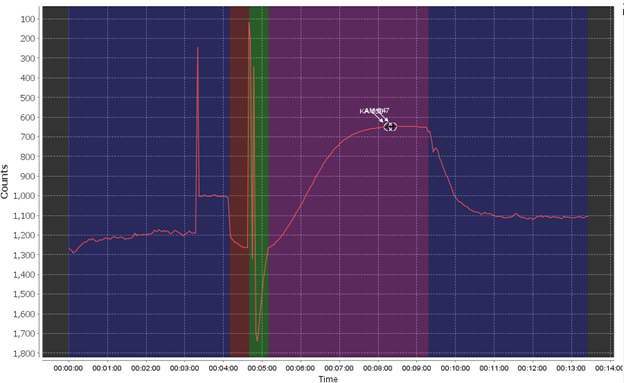

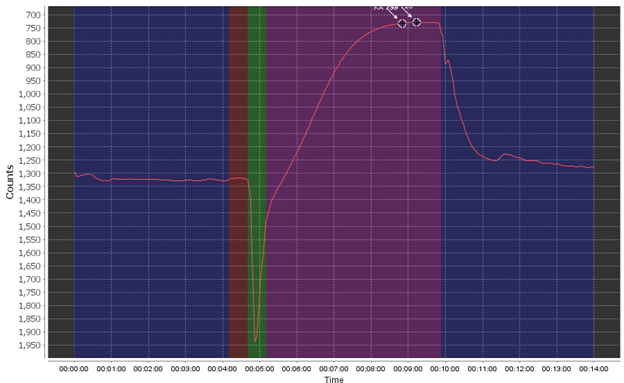

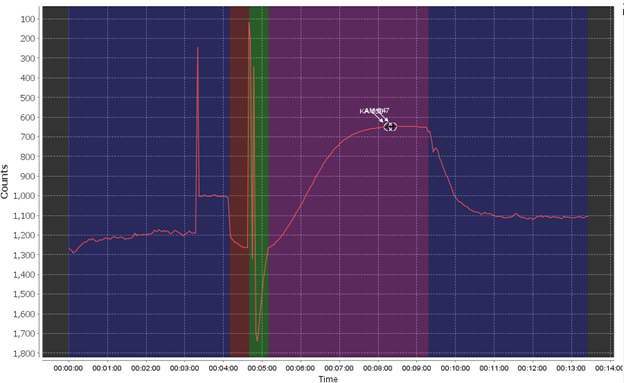

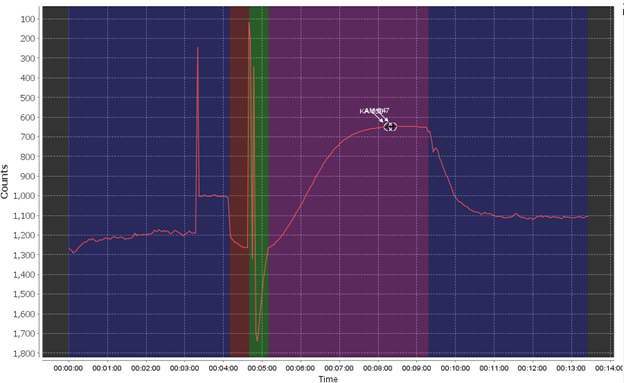

First off, let’s see what a relatively good Raw Data Plot looks like.

The different phases are the pre-flush phase (dark blue), the ambient baseline reading period (red), the sample reagent pump phase (green), the sample read/reaction phase (purple), and finally the post-flush phase (dark blue). During a “spiked run” the full set of phases are repeated twice.

Using this as an example, you want to see a flat pre- and post-pump phase, a stable (flat) ambient read phase, and a pronounced smooth reaction curve. You may see small bumps here and there due to very small bubbles or other effects but this can be negligible.

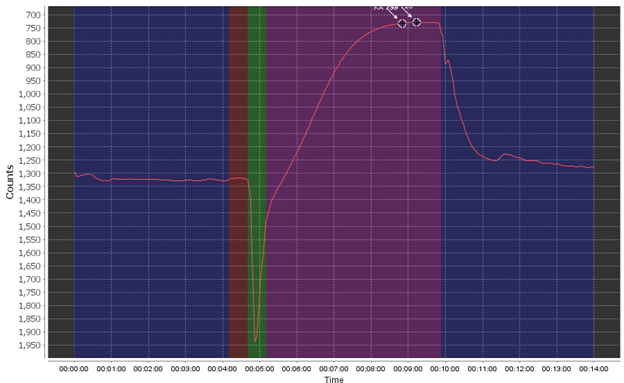

The most common failure mode is the bubble spike flag, which triggers when air is introduced into the system, most commonly through the sample line but possibly through incorrectly installed cartridges or tubing.

The bubble failure is typically identified by large jumps and spikes randomly in the data, primarily in the pre- and post- pump phase and the ambient read phase. Air bubbles create an unstable base line (red) which will affect the sensor’s accuracy. In extreme examples it can completely overshadow the reaction curve as well or shift the baseline to the point where your reaction creates a negative value. Air bubbles often exacerbate other issues, like weak pumps, clogged filters, or already low phosphate in your sample.

Since bubbles can come from a few different places there are multiple checks you can do to try to stop bubbles from appearing in your data. The most important check is ensuring that your hydrocycle is fully submerged for the entirety of your deployment, as the sample line being exposed to air will introduce bubbles.

You should check that each of your reagent carts are fully installed. Press down on each reagent cart until you can hear them click and be careful about applying too much force to any of the plastic pieces that may crack and allow for leaks or air.

You can also test the pump volumes of each reagent and sample to see if your filters are clogged or if there is another issue causing the sample injection system to fail, like a leak. You do so by using Cyclehost’s Pump controls. You should choose all pumps and run each for 100 pumps. A healthy system will pump 1-1.3 ml of reagent and 2.5-3 ml of sample.

If you have bubbles already and need to recover, the most thorough method is to follow our maintenance and cleaning instructions in the manual, primarily the extended flush. Running the extended flush multiple times should be enough to clear bubbles from your system if no other issues are evident.

If doing so still fails to recover your instrument’s counts please reach out to technical support with a copy of your hydrocycle data and brief timeline of events.

For best performance and compatibility, Sea-Bird recommends that customers set their computer to English language format and the use of a period (.) for the decimal symbol. Some customers have found corrupted data when using the software’s binary upload capability while set to other languages.

To update your computer’s language and decimal symbol (instructions are for a Windows 7 operating system):

- In the computer Control Panel window, select Region and Language.

- In the Region and Language window, on the Formats tab, select English in the Format pull down box.

- In the Region and Language window, click the Additional settings . . . button. In the Customize Format window, select the period (.) in the Decimal symbol pull down box, and click OK.

- In the Region and Language window, click OK.

No. An ISUS V2 does not have the correct hardware to be used with ISUSCom. If you have an ISUS V2, and wish to use it with this software, please contact Sea-Bird Scientific Customer Support to discuss upgrading your ISUS.

By default the clock of the StorX is set to UTC time rather than local time.

The StorX will add a UTC timestamp to each data frame that it collects.

The schedule.txt file on board the StorX is a daily schedule, and represents a 24 hour period (00:00 to 24:00). The schedule assumes that the StorX is set to UTC time. The StorX is set to use UTC time by default.

Note that this is especially important if you have a different instrument scheduling for day light hours versus nighttime.

You can check your StorX clock by connecting through the serial connection and using a serial terminal emulator such as hyper-terminal:

First, connect to the StorX serial port, to obtain a command prompt.

From the C:\ prompt, you can verify the StorX clock time by typing “clock get”.

Verify that the date and time provided is correct in UTC time.

If the date and time requires updating, you will first have to use the “date” command to set the PicoDOS time to the correct time in UTC.

Once the PicoDOS time is set correctly, you can then enter a “clock set” command to send the PicoDOS time to the StorX clock.

Be sure to type “clock get” again to verify the time is now correct.

This should be done if the system is not used for some time or performed before a deployment.

Can I install my Sea-Bird CD-ROM on multiple computers or give it to another interested scientist?

You are free to install the software on multiple computers and to give the software to any interested potential user.

Sea-Bird’s Seasoft© software is provided free of charge to Sea-Bird users and is not subject to any license. Seasoft is protected by copyright laws and international copyright treaties, as well as other intellectual property laws and treaties. All title and copyrights in and to Seasoft and the accompanying printed materials, and any copies of Seasoft, are owned by Sea-Bird Electronics. There are no restrictions on its use or distribution, provided such use does not infringe on our copyright.

The software is offered as a download here.

You can plot the raw data from a .dat or .hex file with Seasave V7.

Once the data is converted to a .cnv file with engineering units (using SBE Data Processing’s Data Conversion), you can plot the data in SBE Data Processing’s Sea Plot.

-

Because Sea Plot only works with archived files, it is more sophisticated than Seasave. For example, Sea Plot can provide multiple file overlays, waterfall plots, and TS plots with contours.

If you wish to view the actual numbers you can open the .cnv file (if it was converted as ASCII) with any word processor or text editor.

A .psa (program setup) file is used by Seasave V7 and by each module in SBE Data Processing to remember the way you had the program set up. You can save the .psa file to a desired filename and location, and then use it when you run the software the next time, to ensure that the software will be set up the same way:

- A .psa file is created by Seasave V7 to store program settings, such as the instrument configuration (.con or .xmlcon) file name and path, serial ports, water sampler, TCP/IP ports, serial data output, etc. as well as size, placement, and setup for each display window.

- A .psa file is created by each module in SBE Data Processing to store program settings, such as the input filename and path, output filename, and module-specific parameters (for example, for Data Conversion: variables to convert, ascii or binary output, etc.).

If you want to set up real-time acquisition or data processing on more than one computer in the same way, simply copy the .psa file for the desired setup, and transfer it to the other computer via your network, email, a CD-ROM, or some other media. Then, after you open the software on the second computer, select the .psa file you want to use.

- Seasave V7: Select File / Open Setup File.

- SBE Data Processing: In the module dialog box, on the File Setup tab, click the Open button under Program setup file.

MatLab can import flat ASCII files. To produce those files:

- Run SBE Data Processing’s Data Conversion module to produce a .cnv file with data in ASCII engineering units from the raw data file. This file also contains header information.

- Run SBE Data Processing’s ASCII Out module to remove the header information, outputting just the data portion of the converted data file to a .asc file. Optionally, you can also output the header information to a .hdr file.

Current Sea-Bird software was designed to work on a PC running Windows 7/8/10 (both 32-bit and 64-bit). Sea-Bird provides the software free of charge as part of our instrument support. Because of this, we do not have the resources to write and provide support software for other operating systems, such as Apple, Unix, or Linux.

- If you have a valid PC emulator on your system, the Sea-Bird software may run, but we have no way to confirm this, or that the I/O connections to the instrument will properly function.

- If you have access to a PC running Windows, you can use Sea-Bird’s software to convert the data from our proprietary format to ASCII (in engineering units of C, T, P, etc. with calibration coefficients applied); then you could use your own software on a different computer to perform additional processing.

The flag variable column is added by Data Conversion (if you process data using Sea-Bird software) or ASCII In (if you are importing data that was generated using other software). The Loop Edit module sets the flag variable to bad for scans that show a pressure slowdown or reversal. The flag variable is then used by the rest of the SBE Data Processing modules as an indication of a bad scan, allowing you to exclude scans that are marked bad from processing performed in a module, if desired.

Initially all scans are marked good (flag value of 0) in Data Conversion or ASCII In. A flag of -9.99e-29 indicates the scan has been marked bad by Loop Edit.

Note: All occurrences of the bad value (-9.99e-29) can be replaced with a different value in ASCII Out. This may be useful for plotting purposes, as -9.99e-29 looks like 0 in a data plot.

How does Sea-Bird software calculate conductivity, temperature, and pressure in engineering units?

For formulas for the calculation of conductivity, temperature, and pressure from the raw data, see the calibration sheets for your instrument. If you cannot find the calibration sheets, contact us with your instrument serial number (Click here to see an example of where to find the serial number on your instrument).

The Seasave and SBE Data Processing manuals document the derived variable formulas in an Appendix (Derived Parameter Formulas). The Help files for these programs also document the formulas.<!-- To download the software and/or manuals, go to Software-->.

The formulas are provided in Application Note 69: Conversion of Pressure to Depth.

In Seasoft-DOS version 4.249 and higher (March 2001 and later), January 1 is Julian Day 1. Therefore, noon on January 1 is Julian Day 1.5. Earlier versions of the software incorrectly defined January 1 as Julian Day 0, so noon on January 1 would appear as Julian Day 0.5.

All release versions of SBE Data Processing correctly identify January 1 as Julian Day 1.

Seasoft V2’s Seasave (older software, replaced with Seasave V7 in 2007) created a .dat file from data acquired from the SBE 11plus V2 Deck Unit / SBE 9plus CTD. This also applies to earlier versions of the Deck Unit and CTD.

Some text editing programs modify the file in ways that are not visible to the user (such as adding or removing carriage returns and line feeds), but that corrupt the format and prevent further processing by Seasoft. Therefore, we strongly recommend that you first convert the data to a .cnv file (using SBE Data Processing’s Data Conversion module), and then use other SBE Data Processing modules to edit the .cnv file as desired.

Sea-Bird is not aware of a technique for editing a .dat file that will not corrupt it.

Sea-Bird distributes a utility program, Fixdat, that may repair a corrupted .dat file. Fixdat.exe is installed with, and located in the same directory as, SBE Data Processing.

Note: Seasave V7 creates a .hex file instead of a .dat file from data acquired from the SBE 11plus V2 Deck Unit / SBE 9plus CTD. See the FAQ on editing a .hex file.

Some text editing programs modify the file in ways that are not visible to the user (such as adding or removing carriage returns and line feeds), but that corrupt the format and prevent further processing by Seasoft. Therefore, we strongly recommend that you first convert the data to a .cnv file (using SBE Data Processing’s Data Conversion module), and then use other SBE Data Processing modules to edit the .cnv file as desired.

However, if you still want to edit the raw data, this procedure provides details on one way to edit a .hex data file with a text editor while retaining the required format. If the editing is not performed using this technique, Seasoft may reject the data file and give you an error message.

- Make a back-up copy of your .hex data file before you begin.

- Run WordPad.

- In the File menu, select Open. The Open dialog box appears. For Files of type, select All Documents (*.*). Browse to the desired .hex data file and click Open.

- Edit the file as desired, inserting any new header lines after the System Upload Time line. Note that all header lines must begin with an asterisk (*), and *END* indicates the end of the header. An example is shown below, with the added lines in bold:

* Sea-Bird SBE 21 Data File:

* FileName = C:\Odis\SAT2-ODIS\oct14-19\oc15_99.hex

* Software Version Seasave Win32 v1.10

* Temperature SN = 2366

* Conductivity SN = 2366

* System UpLoad Time = Oct 15 1999 10:57:19

* Testing adding header lines

* Must start with an asterisk

* Can be placed anywhere between System Upload Time and END of header

* NMEA Latitude = 30 59.70 N

* NMEA Longitude = 081 37.93 W

* NMEA UTC (Time) = Oct 15 1999 10:57:19

* Store Lat/Lon Data = Append to Every Scan and Append to .NAV File When is Pressed

** Ship: Sea-Bird

** Cruise: Sea-Bird Header Test

** Station:

** Latitude:

** Longitude:

*END*

-

In the File menu, select Save (not Save As). The following message may display:

You are about to save the document in a Text-Only format, which will remove all formatting. Are you sure you want to do this?

Ignore the message and click Yes. -

In the File menu, select Exit.

This error message typically means that some of the .dll files needed to run the software are installed incorrectly or have been corrupted. We recommend that you remove the software, and then reinstall the latest version.

Note: Use the Windows’ Add or Remove Programs utility to remove the software; do not just delete the .exe file.

The T-C Duct on a 911plus imposes a fixed delay (lag time) between the temperature measurement and the conductivity measurement reported in a given data scan. The delay is due to the time it takes for water to transit from the thermistor to the conductivity cell, and is determined by flow rate (pump rate). The average flow rate for a 9plus is about 30 ml/sec. The Deck Unit (11plus) automatically advances conductivity (moves it forward in time relative to temperature) on the fly by a user-programmable amount (default value of 0.073 seconds), before the data is logged on your computer. This default value is about right for a typical 9plus flow rate. Any fine-tuning adjustments to this advance are determined by looking for salinity spikes corresponding to sharp temperature steps in the profile and, via the SBE Data Processing module Align CTD, trying different additions (+ or -) to the 0.073 seconds applied by the Deck Unit, until the spikes are minimized. Having found this optimum advance for your CTD (corresponding to its particular flow rate), you can use that value for all future casts (change the value in the Deck Unit) unless the CTD plumbing (hence flow rate) is changed.

Oxygen and other parameters from pumped sensors in the same flow as the CT sensors can also be re-aligned in time relative to temperature, to account for the transit time of water through the plumbing. A typical plumbing delay for the SBE 43 DO Sensor is 2 seconds. However, the DO sensor time constant varies from approximately 2 seconds at 25 °C to 5 seconds at 0 °C. So, you should add some advance time for this as well (total delay = plumbing delay + response time). As for the conductivity alignment, the Deck Unit can automatically advance oxygen on the fly by a user-programmable amount (default value of 0 seconds) before the data is logged on your computer. However, because there is more variability in the advance, most users choose to do the advance in post-processing, via the SBE Data Processing module Align CTD. For additional information and discussion, refer to Module 9 of our training class and the SBE Data Processing manual.

Note: Alignment values are actually entered in the 11plus Deck Unit and in SBE Data Processing relative to the pressure measurement. For the 9plus, it is sufficiently correct to assume that the temperature measurement is made at the same instant in time and space as the pressure measurement.

Section 3: Typical Data Processing Sequences in the SBE Data Processing manual provides typical data processing sequences for our profiling CTDs, many moored CTDs, and thermosalinographs. Typical values for aligning, filtering, etc. are provided in the sections detailing each module of the software. This information is also documented in the software’s Help file. To download the software and/or manual, click here: SBE Data Processing.

For formulas for the calculation of conductivity, temperature, and pressure from the raw data, see the calibration sheets for your instrument (if you cannot find the calibration sheets, contact us with your instrument serial number at seabird@seabird.com> or +1 425-643-9866).

For derived parameter formulas (salinity, sound velocity, density, etc.), see the Seasave and SBE Data Processing manuals, which document these formulas in an Appendix. Additionally, the formulas are documented in the Help files for these programs.

In July 2015, Sea-Bird released updated software to address intermittent connectivity issues where the host computer or SeatermV2 cannot recognize an instrument communicating via its internal USB connector. Field Service Bulletin 28 describes the problem and the installation of updated software to solve the problem.

Files that are delivered with Sea-Bird Scientific and third party equipment to describe the sensors data output and calibration coefficients come in two types. Calibration files or *.cal files and telemetry definition format files or *.tdf files. In some cases, systems are created that network many sensors together and their combined data is provided in one serial output. The simplest example is a HOCR sensor that generates both light and dark frames. A more complex example is a HPROII profiling system that may contain as many as 5 sensors and 7 individual calibration and tdf files. These files must be used to both collect and process the data. This can become quite confusing to keep track of all these files so Sea-Bird Scientific developed SIP files. All CAL and TDF files required for a system are zipped using winzip and the extension changed from *.ZIP to *.SIP. The file name includes the system description (usually the network master serial number) and the creation date. This SIP file can then be used in place of individual files to collect and process data.

HOCR sensors output two distinct frame types (light and dark). Thermal dark current changes that occur within the spectrograph are corrected across the full spectrum with the use of a mechanical dark shutter that closes periodically in the radiometer. This creates a unique frame of data that must be collected separately from the light data. SATView requires both calibration files so that it collects both data outputs.

Scientific

The ECO sensors primarily image a volume that is approximately 1 cm3, centered 1 cm off the face of the instrument.

NOTE: This does not preclude return of photons from outside of this volume and in particular it is best that no fixed objects are in the field of view of the instrument, such as cables or cage hardware.

We recommend that the instruments be mounted in such a way that they are seeing only the free field. Often when mounted on a CTD, mounting the ECO face-down or away from the CTD can improve reading accuracy.

That said, the ECO’s have been used in fairly tight quarters with excellent results, including in flow-through housings and dense instrument cages.

When the ECO is mounted in such a way that there is an object in front of the Instrument, the ‘wall effect’ should be established. We are assuming that the material does not fluoresce.

To establish the “wall effect”:

1) Turn the instrument on in air, or better, in a clear water bath, and collect an ‘offset’ reading.

2) Compare this to the factory calibration offset. If the difference is small (e.g. a few counts or mV), then no further action is necessary.

3) Rotate the instrument to find the minimum offset. The backscattering or turbidity channel is the best for this.

4) Mark this position and record the output values of all channels.

5) To minimize the wall effect any object in front of the face of the instrument should be dull black or grey. Tape is usually the easiest solution for this on frames. Grey or black matte plastic is the solution for underway systems.

6) Use these values as the offset values in generating engineering unit output, as specified on the characterization sheets:

Output = ScaleFactor x [InstrumentOutput – Offset]

7) After collecting data from the field, check to confirm that the offset you are using is appropriate. You may find that your minimum values are lower than the offset you have established.

The deep SBE41 and SBE61 use the same pressure sensor – a 7000dbar Kistler. And, they are calibrated with the same Paroscientific Digiquartz reference. However, the calibration process is different. A deep SBE41 receives a 2-point sensor only temperature compensation for pressure. The initial accuracy for a deep 41 is +/- 7dbar, typical stability is 2dbar/year. A 61 receives a 4-point temperature compensation for pressure after the instrument is completely assembled, such that the correction includes both the sensor and the electronic boards. The initial accuracy for a 61 is +/-4.5dbar, typical stability is 0.8dbar/year.

The pH sensor will be shipped dry but was pre-conditioned in seawater (generally from Pacific Ocean waters near Hawaii). While conditioning and evaluating the pH sensor, only expose it filtered, sterilized natural seawater. Do not use seawater CRMs (Certified Reference Material), synthetic seawater, deionized water, NaCl Solutions, or tap water.

Before pre-deployment testing, you will need to fill the plumbing around the pH sensor with natural seawater. The pH sensor needs time to acclimate to the ionic concentration of region specific waters. Once wet, the time to recondition the sensor so that it will report within its accuracy specification depends on several factors, including the ionic composition of the seawater used and the amount of time the pH sensor was stored dry. This time can range from several hours to up to three days.

When the seawater bridge between Counter Electrode and ISFET is broken for longer than 10 seconds, it will be necessary to re-condition the sensor. The sensor does not require recalibration after being re-conditioned.

To prepare the sensor for deployment, it is recommended that several days prior to deployment, the isolated battery is connected via the float interface and the pH sensor is stored in water that is similar to the deployment site. The sensor should be stored dry to avoid bio-fouling of the ISFET and the battery may be removed during storage. Seawater creates a half cell bridge between the Counter Electrode and ISFET, and power to that circuit is provided by the isolated 9V cell. Without seawater, the battery is unnecessary and may be disconnected.

Cells that have been contaminated with foreign material generally read low of the actual conductivity. Your zero (in air) conductivity reading is generally unaffected.

The conductivity error due to fouling will generally be proportional to the conductivity value. Conductivity is corrected not as an offset but as a ratio (multiplicative) error compared to a reference.

Salinity is a derivative measurement of temperature, conductivity, and pressure, and should be corrected by adjusting the component measurements. Generally speaking, an error in the conductivity measurement will correlate to a directly proportional error in the salinity measurement.

The temperature and salinity correction for the SUNA can be traced to the experiment outlined in Sakamoto et al. 2009, which is the T/S correction our UCI-based SUNA software uses in post-processing only.

Absorption of UV light in seawater is dominated by dissolved nitrate and bromide ions at wavelengths less than 240 nm. To estimate nitrate, it is necessary to remove the absorption due to bromide. The salinity correction addresses the sea salt extinction coefficients due to bromide. In the real ocean, bromide covaries with NaCl. So, during calibration, we can measure the the bromide absorption due to seawater at one salinity and later predict the absorption due to seawater at any salinity.

Artifical seawater surrogates do not necessarily have the correct bromide absorption to be able to validate the the Sakamoto et al. 2009 salinity correction, so the salinity correction may not product accurate results if your data was not collected in natural seawater.

The SeaFET and SeapHOx systems are designed to sample at a fixed depth. If you want to run discreet samples at depth intervals, you will need to find a way to move the system to a specific depth before each sample interval and stop the descent / ascent for the entire pumping and sampling cycle to get a valid CTD / pH / Oxygen sample.

If you are able to communicate with the system through the serial I/O during profiling, you can send a sampling command to the sensor at each depth point and allow it to complete its sample cycle. Consult the manual for each model for the length of time required to complete each sample. Once the sensor provides a sample, you can then move it to the next depth point and repeat.

If you aren’t running real-time communications to the SeaFET/SeapHOx, you could also set it to autonomously sample at a time interval that gives you enough time to move the package to a new depth point between sample cycles. The challenges with this approach would be to know exactly when the sensor is sampling without any direct feedback from the instrument.

SUNAs ordered with the 5mm path length coupler as a factory option will perform much better in low light transmission waters due to the shorter length the light needs to travel leading to less absorption. Equipping your SUNA with the factory bio-wiper option will also perform better and be less susceptible biofouling or buildup of other material that can reduce light transmission.

There are also some maintenance practices and device settings that can give SUNA a better probability of being able to capture enough light for a sample. Enable adaptive integration will trigger the SUNA to increase the lamp on time when light received by the spectrometer is low. It is also important to clean the windows as frequently as possible and monitor lens for scratches. Finally, you want your maximum light spectral counts at the peak wavelength (around 240nm) to be between 45,000 and 55,000 counts in pure or deionized water. This can be viewed in the “Spectra” tab in UCI when sampling or replaying data. If your peak spectrometer output is below 45,000 counts after cleaning the window, you may increase the integration period by 25 to 50 ms if needed (but not more; further changes require a factory recalibration). After adjusting the integration period, always perform a reference spectrum update per the instructions in the SUNA manual.

The ISFET has two reference electrodes: an internal reference and an external reference, that give separate reference potentials to the ISFET and show separate pH values (pH Internal and pH External). After the corrections for temperature and salinity are applied, the values from the internal and external are similar, and let the user verify the validity of the sensor’s measurements.

Internal reference:

The internal reference electrode inside the DuraFET® is immersed in a bath of saturated potassium chloride (KCl) gel and is physically separated from the environment. The KCl gel exposes the Ag/AgCl internal electrode to a relatively constant chloride concentration. The sensor can therefore measure pH regardless of environmental salinity. If accurate salinity and temperature data are not available, the internal cell is generally more accurate.

External reference:

The external reference electrode has a Ag/AgCl reference electrode in direct contact with seawater. The potential of this electrode varies with pH and chloride concentration, so unless the chloride concentration is known, the external reference is not stable. To correct this, salinity can act as an approximation of chloride concentration. If accurate salinity data is available, it can be applied to the pH external data and significantly reduce measurement errors, and give the most accurate and stable pH data.

Artificial seawater is problematic because the salts in artificial seawater do not completely dissolve leaving you with a solution that does not completely match the ionic concentration of seawater. This is true for synthetic blends (made for aquariums) or ones made from drying natural seawater. The different ionic concentration leads to drift and potential offsets in the pH sensor. This leads to an inaccurate K0 and initial drift in the external reference of the pH sensor, the internal reference electrode should be unaffected because it separated from the seawater by a saturated solution of KCl gel. This occurs because the pH sensor external reference electrode is a solid state AgCl electrode which is in direct contact with the seawater. A unconditioned Ag/Cl external electrode K0 typically changes by 3mV (60mpH) when exposed to natural seawater for the first time. The challenge here is without knowing the ionic composition of the artificial seawater it is difficult to determine exactly how long the drift will occur or if there will be a permanent offset. This is why we recommend to only use natural seawater.

When the Ag/AgCl is first installed in the sensor it is pure Ag/AgCl, but when it is exposed to seawater it reacts with the ions (Br- mostly, but there are other ions too) in seawater which changes its ionic composition and its standard potential. The standard potential is the K0 coefficient which is provided to the customer and the manufacturer the sensors in seawater for ~3 days in natural seawater to ensure the external electrode is conditioned to seawater prior to K0 calibration in seawater baths. If the sensor is then put into artificial seawater with the incorrect ionic compositions, you risk deconditioning the external reference which could lead to inaccurate measurements and drift in the sensor when first deployed. The sensor should recondition to seawater after deployment. The reconditioning can take 3 days to 2 weeks, however permanent offsets can remain even after the external reference has stabilized.

However, if you cannot obtain natural seawater on a regular basis. You could obtain some natural seawater when the pH sensor is recovered or deployed. The seawater could be taken back to your lab, filtered and stored in a dark container in a cool and dark place for a couple months. Just be sure to filter the seawater again before you fill the wet cap to store the pH sensor for long periods of time.

The measurement range and accuracy of the SBE43 are not defined in discrete units (mL/L, mg/L, µMol/L, etc.) Rather, the range and accuracy specification are expressed as a ratio of the calculated oxygen saturation point. This saturation value depends on the temperature and salinity of the water, decreasing in higher temperatures and higher salinities.

The more detailed answer is a theoretical maximum value can be calculated. While the absolute maximum value would need to be calculated using the highest value one could select as a reference saturation point in natural waters, this theoretical maximum value’s calculation is demonstrated below:

10.84 ml/l (15.49 mg/l) the oxygen saturation point for

In the coldest (-2°C) and least saline (0 PSU) water, the oxygen saturation point is 10.84 ml/l (15.49 mg/l. Using this as a reference saturation point, 10.84 ml/l is multiplied by 1.2 to make 13.01 ml/l (18.59 mg/l), or 120% of the oxygen saturation; this represents the upper end of the measurement range in the given water and can be called the theoretical maximum value for the sensor.

The measurement range and accuracy of the SBE43 are not definite in discrete units (mL/L, mg/L, µMol/L, etc.) Rather, the range and accuracy specification are expressed as a ratio of the calculated oxygen saturation point. This saturation value depends on the temperature and salinity of the water, decreasing in higher temperatures and higher salinities.

The lower limit of detection of dissolved oxygen concentration is going to be constrained by the accuracy specification, which is a ratio of the calculated oxygen saturation (initial accuracy: +/- 2% of saturation). This saturation value varies depending on the temperature and salinity of the water. Common oxygen saturation values in seawater are in the range of 4-7 mL/L. Using this value as an estimate, you can extrapolate that the accuracy of the sensor in many conditions can be as low as +/- 0.1 mL/L. Therefore, the close you get to zero oxygen concentration, the closer the resolution of your measurement will be to the accuracy spec, until you get below 0.1 – 0.2 mL/L and your measured value is smaller than the nominal error margin.

While the theoretical lower limit of the instrument’s measurement range is zero, the measurement becomes less meaningful the closer your dissolved oxygen measurement gets to 2% of the calculated saturation. For example, if you were in an environment where the oxygen saturation was 7 mL/L but the oxygen concentration measured by the SBE43 was 0.28 mL/L, then your accuracy would effectively be +/- 50% of the measurement.

The ECO-PAR, due to the nature of PAR sensors, cannot be accurately calibrated outside of the Sea-Bird facility. However, there are some functionality tests that can aid in pre-deployment.

A bright flashlight can validate whether the instrument sees light at all.

On a bench test one should see between 1000-4000 counts normally with the instrument in the white cap standing up on the benchtop. Use a terminal program to see the raw counts, such as Tera Term, and point a flashlight beam near the white cap. Doing so with a functioning unit will cause the counts to go to approximately a couple of thousand in a hair trigger fashion. It should be possible to decrease the counts on a properly functioning instrument by cupping ones hands around the white cap to shield it from light. It should be easy to get a response of a couple of hundred counts total in doing this. In the field if you shine a flashlight beam directly into the optics will see low level ambient light and it is easy to regulate the output in counts at the low end of the range (less than 1000 counts) when it is functioning normally. If your unit is not properly functioning, it will go from 50-ish to a couple of thousand counts and it will be very difficult or impossible to get an output of a couple of hundred counts. While the ranges of the response may differ between PAR models, these tests can be used with other PAR sensors to verify operation.

The ECO-PAR, due to the nature of PAR sensors, cannot be accurately calibrated outside of the Sea-Bird facility. However, there are some functionality tests that can aid in pre-deployment. A bright flashlight can validate whether the instrument sees light at all.

On a bench test one should see between 1000-4000 counts normally with the instrument in the white cap standing up on the benchtop. Use a terminal program to see the raw counts, such as Tera Term, and point a flashlight beam near the white cap. Doing so with a functioning unit will cause the counts to go to approximately a couple of thousand in a hair trigger fashion. It should be possible to decrease the counts on a properly functioning instrument by cupping ones hands around the white cap to shield it from light. It should be easy to get a response of a couple of hundred counts total in doing this. In the field if you shine a flashlight beam directly into the optics will see low level ambient light and it is easy to regulate the output in counts at the low end of the range (less than 1000 counts) when it is functioning normally. If your unit is not properly functioning, it will go from 50-ish to a couple of thousand counts and it will be very difficult or impossible to get an output of a couple of hundred counts. While the ranges of the response may differ between PAR models, these tests can be used with other PAR sensors to verify operation.

There are two optional modifications that can be done to your 9p at our facility (during service or as part of your original order) that will allow the 9p CTD to operate in freshwater deployments. The 9p’s pump will not operate in freshwater without these options.

First, the Modem Pump Control, allows you to control the pump directly, bypassing the requirement for it to see a certain conductivity frequency to activate. (On other CTD’s we can change this conductivity value to allow both freshwater and saltwater).

The second option is the freshwater contact pin, an optional pin modification that allows for the detection of fresh water by the 9p.

Cells that have been contaminated with foreign material generally read low of the actual conductivity. Your zero (in air) conductivity reading is generally unaffected.

The conductivity error due to fouling will generally be proportional to the conductivity value. Conductivity is corrected not as an offset but as a ratio (multiplicative) error compared to a reference.

Salinity is a derivative measurement of temperature, conductivity, and pressure, and should be corrected by adjusting the component measurements. Generally speaking, an error in the conductivity measurement will correlate to a directly proportional error in the salinity measurement.

The temperature and salinity correction for the SUNA can be traced to the experiment outlined in Sakamoto et al. 2009, which is the T/S correction our UCI-based SUNA software uses in post-processing only.

Absorption of UV light in seawater is dominated by dissolved nitrate and bromide ions at wavelengths less than 240 nm. To estimate nitrate, it is necessary to remove the absorption due to bromide. The salinity correction addresses the sea salt extinction coefficients due to bromide. In the real ocean, bromide covaries with NaCl, so we can measure (during calibration) the the bromide absorption due to seawater at one salinity and later predict the absorption due to seawater at any salinity.

Artifical seawater surrogates do not necessarily have the correct bromide absorption to be able to validate the the Sakamoto et al. 2009 salinity correction, so the salinity correction may not product accurate results if your data was not collected in natural seawater.

The measurement range and accuracy of the SBE43 are not defined in discrete units (mL/L, mg/L, µMol/L, etc.) Rather, the range and accuracy specification are expressed as a ratio of the calculated oxygen saturation point. This saturation value depends on the temperature and salinity of the water, decreasing in higher temperatures and higher salinity.

The lower limit of detection of dissolved oxygen concentration is going to be constrained by the accuracy specification, which is a ratio of the calculated oxygen saturation (initial accuracy: +/- 2% of saturation). This saturation value varies depending on the temperature and salinity of the water. Common oxygen saturation values in seawater are in the range of 4-7 mL/L. Using this value as an estimate, you can extrapolate that the accuracy of the sensor in many conditions can be as low as +/- 0.1 mL/L. Therefore, the close you get to zero oxygen concentration, the closer the resolution of your measurement will be to the accuracy spec, until you get below 0.1 – 0.2 mL/L and your measured value is smaller than the nominal error margin.

While the theoretical lower limit of the instrument’s measurement range is zero, the measurement becomes less meaningful the closer your dissolved oxygen measurement gets to 2% of the calculated saturation. For example, if you were in an environment where the oxygen saturation was 7 mL/L but the oxygen concentration measured by the SBE43 was 0.28 mL/L, then your accuracy would effectively be +/- 50% of the measurement, making it relatively useless.

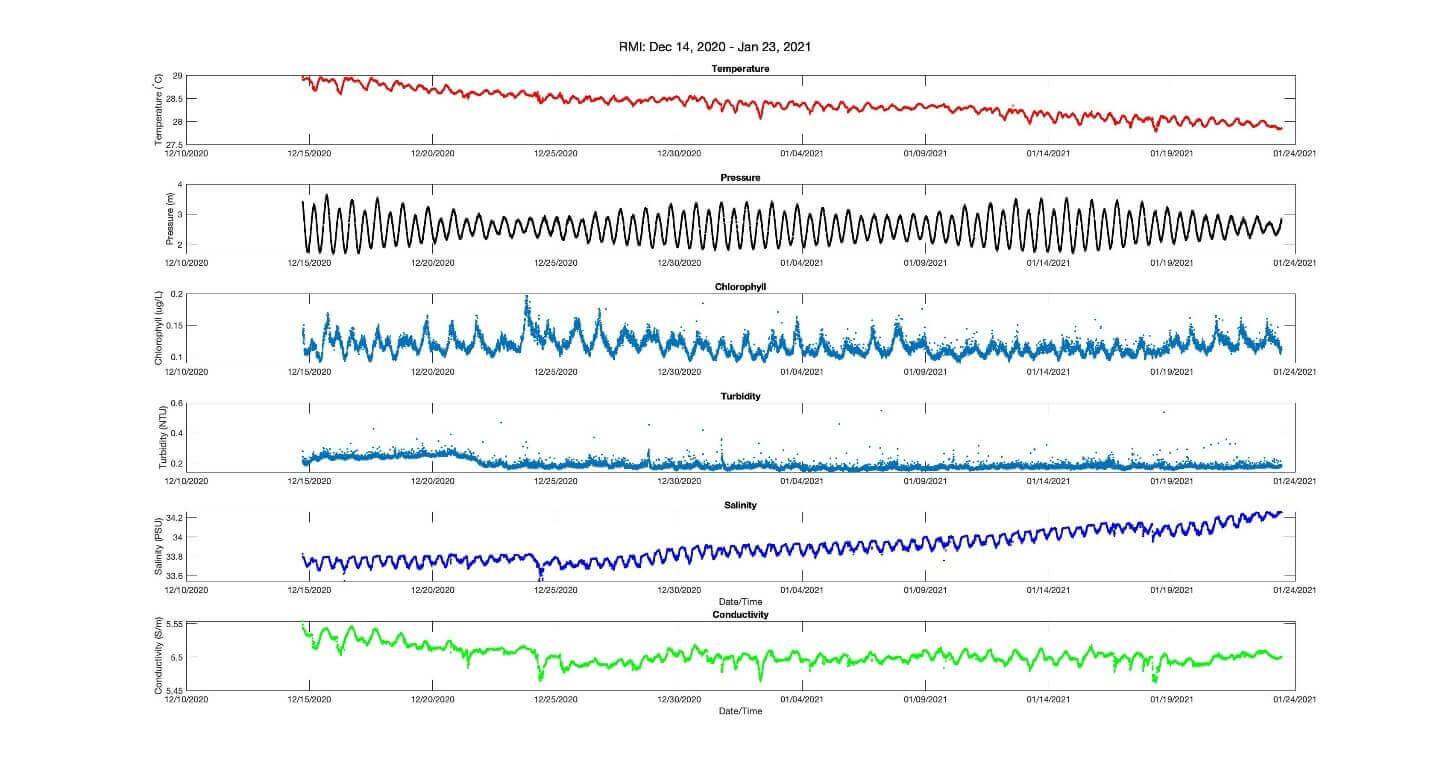

Example Data:

Temperature and Conductivity are two of the most important values taken into consideration when our instrument calculates the practical salinity of seawater. When one sees a change in a measured value, such as temperature, that change will affect your salinity reading in a predictable way, assuming all else is equal. For instance, in an environment where temperature has begun to drift downward you will see a resulting drift of salinity towards being saltier.

Proper cleaning procedures, allowing your CTD to equilibrate at the surface before a profile, updating your calibrations yearly, and bio-fouling prevention are some ways that you can ensure that your instrument will provide accurate salinity data.

A vented copper cover over the sensor can provide some protection against bio-fouling. There is a copper anti-foul guard available for standalone SeaFETs that covers the sensing surfaces.nnIf you use a SeapHOx system, the conductivity cell on the SBE 37-SMP comes equipped with TBTO anti-foul devices at the sample intake and exhaust. These devices will provide a further degree of fouling protection for the ISFET sensor in the pumped flow path. For best results, we recommend replacing the TBTO anti-foul devices before each deployment.nnThere are some antifouling systems that are not recommended:nnWe recommend against electro-chlorination systems. Stray currents in the water could damage the ISFET. Also, adding electrical potential could disrupt the feedback loop between the ISFET and the counter electrode, causing unreliable pH measurements. Finally, a electro-chlorination system doesn’t create just chlorine species, it creates any ions possible in seawater with a lower standard potential then the voltage you are applying. This will create a number of ionic species that will affect the pH of the sample, thereby causing your pH measurements to be inaccurate. In general, we would not recommend putting a ISFET pH sensor inline or downstream from a seawater electrolysis system.nnWe also recommend against UV anti-fouling systems with a SeaFET. There is a risk of exposing the chip to UV radiation, which can cause damage.

The temperature and salinity correction for the SUNA can be traced to the experiment outlined in Sakamoto et al. 2009, which is the T/S correction our UCI-based SUNA software uses in post-processing only.nnAbsorption of UV light in seawater is dominated by dissolved nitrate and bromide ions at wavelengths less than 240 nm. To estimate nitrate, it is necessary to remove the absorption due to bromide. The salinity correction addresses the sea salt extinction coefficients due to bromide. In the real ocean, bromide covaries with NaCl, so we can measure (during calibration) the the bromide absorption due to seawater at one salinity and later predict the absorption due to seawater at any salinity.nnArtifical seawater surrogates do not necessarily have the correct bromide absorption to be able to validate the the Sakamoto et al. 2009 salinity correction, so the salinity correction may not product accurate results if your data was not collected in natural seawater.

Yes, provided the SeaFETTM sensing elements remain ice-free, the instrument works across the broad temperature range of 0 to 50 deg C. The original SeaFETTM prototypes developed at MBARI and SCRIPPS were deployed extensively in the Antarctic for several studies. For example times series data, please see Matson et al. 2011.

For SBE 4 conductivity calibrations, Sea-Bird uses natural seawater that has been carefully collected, stored, UV irradiated, and filtered. Artificial seawater is not adequate if calibration errors are to be kept below 0.010 psu.

Note: SBE 4 is the conductivity sensor in the SBE 9plus, 25, and 25plus profiling CTDs.

The primary difference between natural and artificial seawater is the behavior of conductivity versus temperature. The practical salinity scale 1978 equations include a term rt. This term is expanded into a fourth order equation that describes the variation of conductivity versus temperature for a sample of constant salinity. The equation’s coefficients are derived by fitting to natural seawater samples. Artificial seawater does not have the same conductivity versus temperature characteristic, providing incorrect coefficients and causing a slope error in the calibration.

For calibrations of conductivity sensors other than the SBE 4, Sea-Bird uses artificial seawater (NaCl solution). However, we place an SBE 4 conductivity sensor in each bath, providing a standard for reference to the natural seawater calibration. This allows us to correct errors in the coefficients and slope introduced with the artificial seawater calibration.

For calibration of temperature sensors, Sea-Bird uses artificial seawater (NaCl solution).

The difference between downcast and upcast is most likely related to package wake. When the CTD is mounted under a large water sampler, the variation can be on the order of 5 to 8 meters. This is due to the shadowing of the CTD sensors by the water sampler.

One of the reasons that this is not a simple question is that there are several factors to take into consideration regarding the error margin for practical salinity measurements. Salinity itself is a derived measurement from temperature, conductivity, and pressure, so any errors in these sensors can propagate to salinity. For example, our initial accuracy specification for the SBE 3plus temperature sensor and SBE 4 conductivity sensor on an SBE 9plus CTD is approximately equivalent to an initial salinity accuracy of 0.003 PSU (note that conductivity units of mS/cm are roughly equivalent in terms of magnitude to PSU).

However, another issue to consider is that this accuracy is defined for a clean, well-mixed calibration bath. In the ocean, some of the biggest factors that impact salinity accuracy are 1) sensor drift from biofouling or surface oils for conductivity in particular and 2) dynamic errors that can occur on moving platforms, particularly when conditions are rapidly changing, which will be true for all sensors that measure salinity. Sea-Bird provides recommendations, design features such as a pumped flow path, and data processing routines to align and improve data for the salinity calculation to account for thermal transients and hysteresis, and to match sensor response times. Depending on the environment and the steepness of the gradient, and after careful data processing, this may continue to have an impact on salinity on the order of 0.002 PSU or more, for example. For more details, see Application Note 82.

Lastly, note that salinity in PSU is calculated according to the Practical Salinity Scale (PSS-78), which is defined as valid for salinity ranges from 2 – 42 PSU.

The FIRe System measures changes in chlorophyll fluorescence that occur during a short (100 – 400 ?s) but intense (> 20,000 ?mol photons m-2 s-1) flash of light whereas the PAM approach measures the fluorescence induced by a weak modulated light source while using ‘saturating’ pulses of ~3000 – 10,000 ?mol photons m-2 s-1 to modify fluorescence yields.

The FIRe System also fundamentally differs from a PAM in that the FIRe fully reduces the primary electron acceptor, QA, allowing a simultaneous single closure (STF) event of all photosystem II (PSII) reaction centers whereas the PAM technique generates multiple photochemical charge separations (MTF) that fully reduces QA, the secondary acceptor, QB, and plastoquinone (PQ). By lengthening the measuring protocol the FIRe can also yield MTF data.

For a complete discussion on the mechanistic and practical differences between the two techniques see: Suggett, D.J., K. Oxborough, N.R. Baker, H.L. MacIntyre, T.M. Kana, & R.J. Geider. 2003. Fast repetition rate and pulse amplitude modulation chlorophyll a fluorescence measurements for assessment of photosynthesis electron transport in marine phytoplankton. European Journal of Phycology. 38: 371-84.

Sea-Bird Scientific has developed cosine collectors that are specifically designed to optimize performance in the intended media of operation (air or water). So in water irradiance sensors have cosine collectors that provide an excellent response in water but not in air. In air irradiance sensors provide an excellent cosine response in air but not in water.

Sea-Bird Scientific multispectral 500 series radiometers measure light at each fixed wavelength with an interference filter/detector assembly. The analog output of each detector is amplified and digitized. The amplification stage and noise filtering is fine tuned for each wavelength to produce an optimal saturation limit and frame rate. This maximizes the signal to noise ratio while ensuring that each channel does not saturate during normal operations. The frame rate of each radiometer is fixed anywhere between 1 and 24 Hz depending on the customers specific requirements. 4 and 7 channel radiometers can be purchased in several configurations with different field of views. They have a small diameter to reduce self-shading and generate a digital output for stand-alone operations or they can operate as part of a larger 485 network of sensors (SATNet). 500 series sensors are also very low power devices making them excellent sensors for power limited platforms such as buoys, AUV’s and profiler floats.

Sea-Bird Scientific Hyperspectral HOCR radiometers use a Zeiss spectrograph optimally configured and characterized to measure light between 350 and 800 nm (approximately 136 individual channels). With the HOCR series, a variable integration time is used for all channels in the array and upper and lower thresholds are set so that no channel saturates within that array. Thermal dark current changes that occur within the spectrograph are corrected across the full spectrum with the use of a mechanical dark shutter that closes periodically in the radiometer. A separate frame of data is generated for this dark reading. Frame rates are dependent on the integration time of the device so are considered variable. When light levels are high, the integration time and frame rate are also high, so that you are collecting many frames per second. As the light level decreases, the integration time must increase and therefore the frame rate becomes longer. Integration times range from 4 ms to 2 seconds. HOCR sensors also have a small diameter to reduce self-shading and the same telemetry options are offered. Sea-Bird Scientific also offers a low power, non-SATNet version of the HOCR sensor for remote platforms that are power limited.